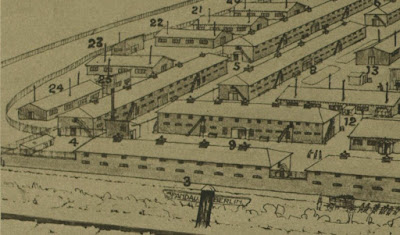

I was updating a talk last night for the forthcoming Family History Foundation's Really Useful Virtual Family History Show (www.fhf-reallyuseful.com) on November 14th, in which I will be speaking on the topic of British Civilian POWs in the First World War. This will essentially focus on the story of the Ruhleben camp (pictured below), near Berlin, at which 5500 British civilians, and civilians from the British Empire, were interned for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time when war was declared.

I have a personal connection to the story, in that my Scottish great grandfather, David Hepburn Paton, a Scottish shop manager in Brussels, Belgium, at the outbreak of the war, was forced into hiding to avoid being arrested following the internment order issued by the German government in November 1914. David died in 1916 during his concealment, leaving his wife, Jessie MacFarlane, and three children to live in Brussels with little to no financial support during the remainder of the occupation. In the aftermath of his death, his son John (pictured below) was subsequently arrested and sent to Ruhleben, where he remained for the rest of the war.

I knew about John's time at Ruhleben, and that he had been arrested because he had turned 'of age'. John had been born on 29 October 1898 in Brussels, and a document from the National Archives at Kew had shown that he was taken to Ruhleben on December 1st 1916. No matter how many times I have gone through the documents, however, I discovered something last night that had been staring me in the face for a couple of years that had not initially clicked into place, but which unusually provoked a brief emotional response from me last night of sheer bloody anger.

A couple of years back I obtained a copy of another record concerning John on the Prisoners of the First World War website at https://grandeguerre.icrc.org, an online platform of the International Committee of the Red Cross. There was not a lot of detail on the form, but one I had either weirdly overlooked, or simply hadn't added to another 2 to make 4, was that it listed his date of arrest in Brussels, given as October 31st 1916. Whilst inserting this into the chronology of other records detailing his story last night, I have only just twigged, or perhaps only just remembered, that he was in fact arrested just two days after he had turned 18 years of age.

As family historians, we try to avoid judging events in the past, because we only work in the past and do not live within it, and no matter how hard we try we can never truly understand the contemporary context of happened with any event - we can only pick up the documented pieces afterwards and try to at least gain a glimpse of proceedings. Sometimes phrases may have more meaning in those documents than we at first may determine. In a letter from 1917, an uncle of John's noted that "when of age he was taken away", which I initially just assumed meant that John was at Ruhleben because he was aged 18, but in hindsight, I am now thinking he literally meant that he was recalling the exact experience of how he was taken away when he turned 18, which must have been a traumatic moment in time for the whole family.

But it wasn't as a family historian that I became angry last night, it was as a parent. Right now I have two sons, about to turn 16 and 20, so John was halfway between their two ages at the time he was lifted. Having just become what the authorities recognised as a man in a legal sense, he was taken, perhaps dragged, from his mother and siblings, for the crime of simply turning 18, and transported from his home in Brussels to another country, where another language was spoken by the authorities, to spend a month at the Berlin based Stadtvogtei prison, before being taken to Ruhleben.

What must have been going through his mind? What must his recently widowed mother been going through in Belgium, and my grandfather (aged just 12 at the time), and their sister?

And what if this had happened to one of my boys?

I have no photograph of my great grandmother Jessie, I have just one letter written by her from Brussels during the occupation in which she noted that my grandfather, as a young boy, was "ill from privation", she barely having the means to survive financially. I have a few facts about her life afterwards back in Scotland following the war, in Glasgow and Inverness, but beyond that, she remains mainly a technical construct, the product of a few documents, giving me a glimpse into who she might have been in a factual sense. But last night, I got another glimpse of her, a brief emotional insight into what she must have experienced. In perhaps just a minor way, and for a short moment, it elevated my understanding of her beyond anything a single document could reveal.

Last night, Jessie Paton nee MacFarlane (1866-1948) wasn't just my great grandmother, she was my grandad's mum, a parent who like many of us will have had to overcome adversity to enable a future for her kids. Thanks Jessie.

For more on my talk, British Civilian POWs in World War One, and for details of other talks and speakers at the FHF event on November 14th, visit www.fhf-reallyuseful.com/speakers/. We'll hopefully see you there!

Chris

My next 5 week Scotland 1750-1850: Beyond the Old Parish Registers course starts November 2nd - see https://www.pharostutors.com/details.php?coursenumber=302. My book Tracing Your Scottish Family History on the Internet, at http://bit.ly/ChrisPaton-Scottish2 is now out, also available are Tracing Your Irish Family History on the Internet (2nd ed) at http://bit.ly/ChrisPaton-Irish1 and Tracing Your Scottish Ancestry Through Church and State Records at http://bit.ly/ChrisPaton-Scotland1. Further news published daily on The Scottish GENES Facebook page, and on Twitter @genesblog.

No comments:

Post a Comment